The Sami people, indigenous to the Arctic regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia, have long been defined by their deep connection to reindeer, the rhythms of the polar night, and an ongoing struggle to preserve their cultural identity. Their story is one of resilience, adaptation, and quiet defiance in the face of modernization and political pressures.

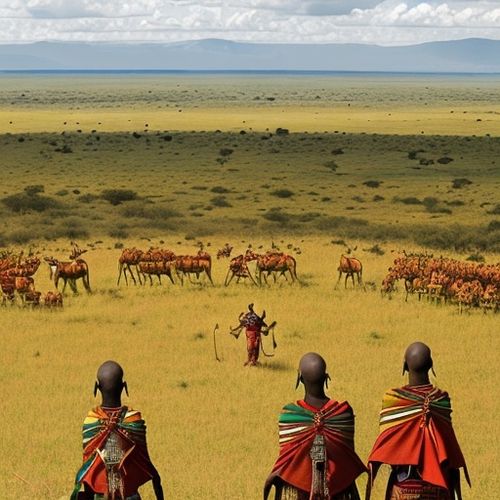

For centuries, reindeer herding has been the cornerstone of Sami life. These animals are not merely livestock but central to their spiritual and economic existence. The Sami follow the migratory patterns of the herds across vast tundras, a practice that demands an intimate knowledge of the land. "Without the reindeer, we would not be Sami," says Nils Mathis, a herder from Kautokeino. The bond between herder and animal is profound—reindeer provide food, clothing, and materials for tools, but they also carry cultural significance, woven into Sami mythology and oral traditions.

Yet this way of life is under threat. Climate change has disrupted migration routes, with warmer winters causing unpredictable ice conditions that make crossings dangerous. Industrial development, including mining and wind farms, encroaches on grazing lands. Many herders now use snowmobiles and GPS to track their herds, blending tradition with necessity. The challenge lies in balancing progress with preservation. Some fear that without intervention, reindeer herding—and the culture it sustains—could vanish within generations.

Winter in the Arctic brings the polar night, a period when the sun does not rise for weeks. To outsiders, this might seem bleak, but for the Sami, it is a time of reflection and community. The darkness is punctuated by the glow of lanterns, the warmth of lavvu (traditional tents), and the storytelling that keeps their history alive. "The polar night teaches patience," explains elder Marit Somby. "It reminds us that light will return, just as our people endure." Festivals like Jokkmokk’s winter market become vital gatherings, where Sami artisans sell duodji (handicrafts) and joik (traditional songs) echo through the cold air.

But endurance has not come easily. The Sami have faced centuries of forced assimilation policies. In Norway and Sweden, children were taken to boarding schools where speaking their language was punished. Land rights were ignored as states carved up territories for logging and hydroelectric projects. Even today, disputes over land use simmer. The recent protests against the Fosen wind farm—built on reindeer pastures despite Supreme Court rulings—highlight the ongoing tension between indigenous rights and national energy goals.

Language revitalization efforts offer a glimmer of hope. Sami dialects, once nearing extinction, are now taught in schools and used in media. Artists like musician Sofia Jannok and filmmaker Amanda Kernell bring Sami narratives to global audiences. Meanwhile, political representation grows; the Sami Parliament in Norway advises on policies affecting their communities. Their fight is no longer just about survival—it’s about sovereignty.

The Sami’s story is a testament to the tenacity of indigenous cultures. They navigate the thin ice of modernity while holding fast to traditions that define them. As the Arctic becomes a focal point for climate debates and resource extraction, the world would do well to listen to those who know it best. "We are the guardians of this land," says Mathis, gazing across the snow. "And we are not leaving."

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025

By /May 11, 2025